What is Fiedler’s Contingency Theory?

Contingency Theory states that different group situations call for different leadership styles. Since leaders have a relatively fixed leadership style, an organization must therefore design job situations to match a leader’s traits in order to achieve group effectiveness.

Fiedler’s Contingency Theory is one of the first formalized management theories to demonstrate the importance of selecting leaders based on group goals and dynamics.

While some theories from the early twentieth century like Max Weber’s principles of bureaucracy emphasize standardization and process, Contingency Theory looks closer at how leadership style impacts group relationships and outcomes.

More importantly, the theory outlines exactly how to identify and match leaders and groups. While not commonly referenced in modern workplaces, it’s a key theory underpinning popular leadership training and management systems like DISC popular in Western corporations today.

- Who Fred Fiedler is

- What Contingency Theory is

- How to assess and understand leadership styles

- How to assess group situations

- How to match a group situation with a leadership style

- Real-life applications of Contingency Theory

Who is Fred Fiedler?

Fred Edward Fiedler (1922-2017) was born in Vienna, Austria. Due to his family’s Jewish heritage, he and his family fled Austria in 1937 and settled in South Bend, Indiana. Soon thereafter, Fiedler served for the US Army during World War II.

After the war, he completed two years of clinical psychology training with the Veterans’ Administration and earned his doctorate in Psychology from the University of Chicago in 1949. Next, he spent time working as a professor of Psychology and Education at the University of Illinois.

Then finally, Fiedler became a professor of Psychology and Management and Organization at the University of Washington in Seattle in 1969, staying there for the remainder of his career.

Fiedler’s most prominent work came in 1967 in his publication, “A Theory of Leadership Effectiveness.” He is best known for his work on this subject, including his Contingency Model and the “Least Preferred Coworker (LPC)” scale. As a result of this work, Fiedler has become known as a key contributor to the field of Industrial and Organizational Psychology.1

Contingency Model Explained

In order to achieve group effectiveness, the Contingency Model requires the following three-step process:

- Assess a leader’s leadership style;

- Assess the situation that a leader faces; and

- Match the situation with the leader’s leadership style.

In order to assess a leader’s leadership style, you must first understand how a LPC scale works. Then, after analyzing LPC scale results, you can determine a leader’s leadership style. I’ll go over both of these processes below.

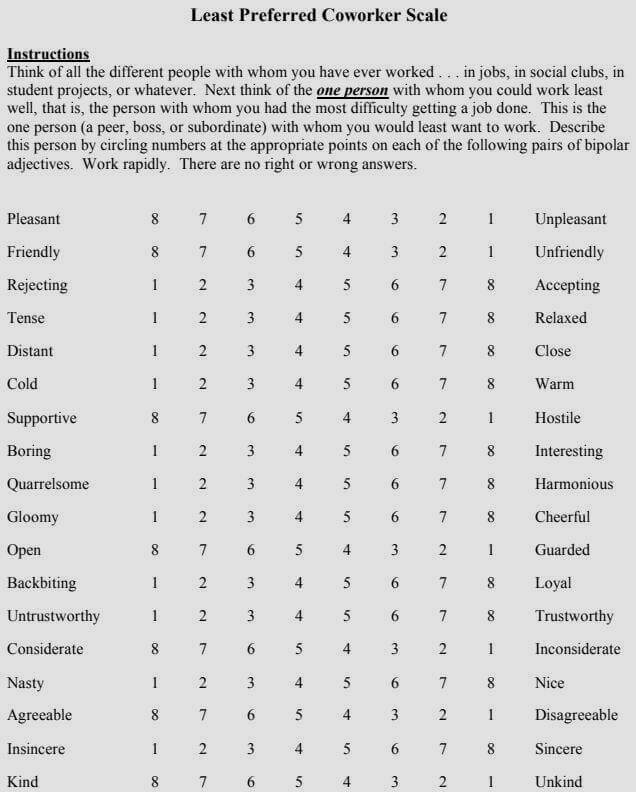

How a Least Preferred Coworker (LPC) Scale Works: Assessing Leadership Styles

Fiedler’s Contingency Model starts with the aforementioned LPC scale.

The way the LPC scale works is a leader is asked to think of their least preferred coworker and rate them on numerous bipolar adjectives. For an example of one adjective, you could select a value between one for “unkind” and eight for “kind” on an eight-point scale of “kindness.”

After the full scale has been completed, the values are totaled to give an LPC score, which is then compared to different ranges to tell the individual their leadership style. The three different leadership styles are:

- Relationship-oriented;

- Task-oriented; or

- Somewhere in-between.2

See below for an example of an LPC scale from the CYFAR Professional Development and Technical Assistance (PDTA) Center. Visit their website to see instructions on how to interpret the LPC score.3

Understanding Leadership Styles from LPC Scale Results

Individuals who have a high LPC score, relationship-oriented leaders, are able to separate the coworker’s personality from poor work performance; that is, they believe someone can perform poorly at work and still have good personality traits. They:

- Are more concerned with establishing good interpersonal relations;

- Are somewhat more considerate;

- Tend to be lower in anxiety;

- Get along better with one another;

- Are more satisfied to be in a group;

- Derive satisfaction from successful interpersonal relationships and enjoy groups regardless of task success; and

- Gain self-esteem through recognition by others.

If a relationship-oriented leader’s needs are threatened, these leaders “will increase [their] interpersonal interaction in order to cement [their] relations with other group members.” Therefore, a relationship-oriented leader will increase focus on the task “in order to have successful interpersonal rations.”

Individuals who have a low LPC score, task-oriented leaders, link a coworker’s personality characteristics to their poor work performance; that is, they believe someone who performs poorly has negative underlying personality traits. They:

- Are more concerned with the task;

- Are more punitive toward poor coworkers;

- Are more efficient and goal-oriented;

- Derive satisfaction from task performance and enjoy groups to a greater degree when they are successful; and

- Gain self-esteem through successful performance of the task.

If a task-oriented leader’s needs are threatened, these leaders will interact in a way that will ensure task success. Thus, a task-oriented leader will increase focus on interpersonal relations “in order to achieve task success.”

Assessing the Situation

In order to assess the situation, Fiedler states that there are three variables that should be considered. The three variables can be described as follows:

- The leader’s position power: “The potential power which the organization provides for the leader’s use”;

- The structure of the task, including:

- “The degree to which the correctness of the solution or decision can be demonstrated” (i.e. decision verifiability),

- “The degree to which the requirements of the task are clearly stated or known” (i.e. goal clarity),

- “The degree to which the task can be solved by a variety of procedures (i.e. goal path multiplicity), and

- “The degree to which there is more than one correct solution (i.e. solution specificity); and

- The interpersonal relationship between the leader and group members, including the leader’s:

- Affective relations with group members,

- Ability to obtain acceptance, and

- Ability to engender loyalty.

Based on these variables, five types of group situations come into existence. They include:

- Informal groups with structured tasks (i.e. structured, weak position power);

- Groups with structured tasks and powerful leader positions;

- Groups within organizations in which leadership is distributed over at least two levels of management (varying conditions);

- Creative groups with unstructured tasks and weak leader position power; and

- Groups with unstructured tasks and powerful leaders.

Matching the Group Situation with the Leadership Style

Fiedler found that “the appropriateness of the leadership style for maximizing group performance is contingent upon the favorableness of the group-task situation.” More specifically, he found that the aforementioned group situations are best matched to the following leadership styles.

| Group Situation | Leader-Member Relations | Leadership Style |

|---|---|---|

| Informal groups with structured tasks | Good | Task-oriented |

| Moderately poor | Relationship-oriented | |

| Groups with structured tasks and powerful leader positions | Good | Task-oriented |

| Moderately poor | Relationship-oriented | |

| Creative groups with unstructured tasks and weak leader position power | Good | Relationship-oriented |

| Moderately poor | Task-oriented | |

| Groups with unstructured tasks and powerful leaders | Good | Task-oriented |

| Moderately poor | Relationship-oriented |

Regarding groups within organizations in which leadership is distributed over at least two levels of management, results were somewhat different. In these cases, when groups had high position power and structured tasks or low position power and unstructured tasks:

- Task-oriented leadership was effective when leader-member relations were either good or poor; while

- Relationship-oriented leadership was effective with moderate leader-member relations.

Altogether, the results of Fiedler’s studies can be best summarized by the following:

- When leader-member relations are moderate, a relationship-oriented leader is best-suited. This is because member relations are in flux and can therefore be positively influenced by the more considerate and personable relationship-oriented leader.

- When leader-member relations are either poor or strong, a task-oriented leader is best-suited. This is due to the task-oriented leader’s objectivity, organization, and decisiveness.45

How the Contingency Model Can Be Applied Today

For the most part, Contingency Theory is relatively intuitive and Fiedler’s book does a great job of providing applications of his theory.

As a first example of applying Fiedler’s model, consider a basketball team, which has a structured task, a low level of power, and (in theory) good leader-member relations. Here, you would want a task-oriented coach to set the game plan rather than a relationship-oriented coach giving everyone an equal say.

As a second example, consider a commercial flight, which has a structured task, a powerful leader, and (in theory) good leader-member relations. Here, you want a task-oriented pilot to take charge; you don’t want a relationship-oriented leader discussing with the group how best to land the plane.

As a third example, consider a creative group with unstructured tasks, weak leader position power, and (in theory) good leader-member relations, like an ad agency. Here, you would want a relationship-oriented leader to get these creative minds to work together rather than a task-oriented leader trying to impose opinions and decisions on the group.

And as a fourth example, consider a squad of soldiers, which has an unstructured task, a powerful leader, and (in theory) good leader-member relations. Here, you would want a task-oriented leader to make decisions and get the group to their objective rather than a relationship-oriented leader who would waste precious time discussing options with the group. As stated in Fiedler’s book about the old army adage, “it is better in an emergency that the leader make a wrong decision than no decision at all.”

So, clearly, Fiedler’s Contingency Model is intuitively accurate and has countless applications across organizations.6

Article Summary

To recap, we covered:

- Who Fred Fiedler was;

- A definition of Contingency Theory;

- How to assess and understand leadership style;

- How to assess a group situation;

- How to match a group situation with a leadership style; and

- Real-life examples of how to apply Contingency Theory.

As you’ve discovered, workplace group situations involve three parties:

- The organization;

- The leader; and

- The group members.

These three parties are said to interact across three dimensions, including:

- Leader-member relations;

- Task structure; and

- Leader position power.

And considering these parties and variables, relationship-oriented leaders are best suited when leader-member relations are moderate, while task-oriented leaders are best suited when leader-member relations are either poor or strong.

While more developments took place after Fiedler’s Contingency Model was published, principles of the model still apply today. As such, it is definitely a worthwhile theory to add to your management theory repertoire.

-

https://tobiascenter.iu.edu/research/oral-history/audio-transcripts/fiedler-fred.html ↩

-

https://openstax.org/details/books/organizational-behavior ↩

-

https://cyfar.org/sites/default/files/Least_PreferredCoworkerScale.pdf ↩

-

https://openstax.org/details/books/organizational-behavior ↩

-

https://openlibrary.org/works/OL3168923W/A_theory_of_leadership_effectiveness?edition=theoryofleadersh00fied ↩

-

https://openlibrary.org/works/OL3168923W/A_theory_of_leadership_effectiveness?edition=theoryofleadersh00fied ↩

30,000 Foot View Definition: Meaning in Business

30,000 Foot View Definition: Meaning in Business